Two Dimensional Kinematics in Normal-Tangential Coordinate Systems

Two Dimensional Motion (also called Planar Motion) is any motion in which the objects being analyzed stay in a single plane. When analyzing such motion, we must first decide the type of coordinate system we wish to use. The most common options in engineering are rectangular coordinate systems, normal-tangential coordinate systems, and polar coordinate systems. Any planar motion can potentially be described with any of the three systems, though each choice has potential advantages and disadvantages.

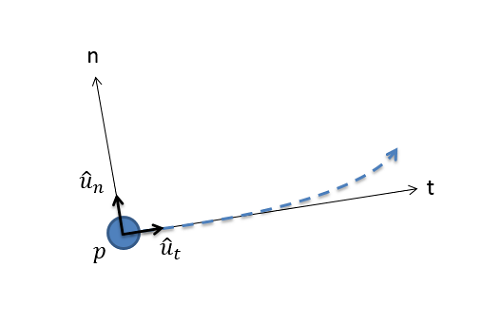

The normal-tangential coordinate system centers on the body in motion. The origin point will be the body itself, meaning that the position of the particle in the n-t coordinate system is always "zero". The tangential direction (t-direction) is defined as the direction of travel at that moment in time (the direction of the current velocity vector), with the normal direction (n-direction) being 90 degrees counterclockwise from the t-direction. The diagram below shows a particle following a curved path with the current normal and tangential directions.

Normal-tangential coordinate systems work best when we are observing motion from the perspective of the body in motion, such as being a passenger in a car or plane. In such cases, we would define ourself as the origin point and "forward" would be the tangential direction. An important distinction between the rectangular coordinate system and the normal-tangential coordinate system is that the axes are not fixed in the normal-tangential coordinate system. If we go back to the car example, the" forward" or tangential direction will turn with the car, but the "east" direction or the x-direction will remain constant no matter which way the car is pointed.

The way the coordinate system is defined, the position of the particle is always set to be at the origin point. The velocity is also always set to be in the tangential direction, and thus there is no velocity in the n-direction. The variable "v"is the body's current speed.

| Position: | \[r_{p/o}(t)=0\hat{u}_{t}+0\hat{u}_{n}\] |

|---|---|

| Velocity: | \[v(t)=v\hat{u}_{t}\] |

To find the acceleration, we need to take the derivative of the velocity function. This may seem simple, but there is a new thing to consider in that the ut unit vector is not constant. This means a change in speed can cause an acceleration or a change in direction (which would change the ut direction) can cause an acceleration. Going back to our car example this makes some intuitive sense. We can feel accelerations, and we would be able to feel acceleration if we suddenly stepped on the gas and increased our speed, but we would also be able to feel the acceleration if we took a tight turn at a constant speed.

Going back to the derivative, we will use the product rule, taking the derivative of one piece at a time.

| \[a(t)=\dot{v}\hat{u}_{t}+v\dot{\hat{u}_{t}}\] |

V dot is the rate of change of speed of the body, which is called the tangential acceleration. Going back to our car analogy this is the acceleration we would experience from pressing the gas or brake pedals.

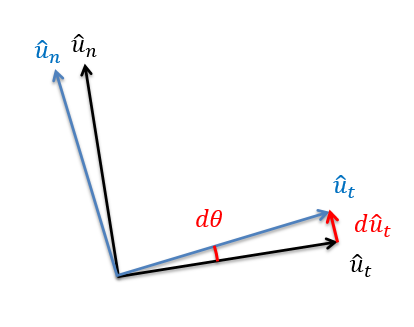

The other piece of our derivative is the speed times the derivative of a unit vector, which we will need to analyze further. When thinking about the derivative of a rotating unit vector, we think about rotating the coordinate system by a small amount d theta.

The derivative of the u-t vector is then the change in position of the head of the vector. Using some geometry, we can see that the distance the head of the vector moves is the length of the vector (which is always 1 for a unit vector) times the angle of rotation in radians. The direction the head of the u-t vector travels is roughly the u-n direction. In fact as d theta approaches zero, it becomes exactly the u-n direction. Putting this back into our derivative we wind up with the following equation for acceleration.

| \[a(t)=\dot{v}\hat{u}_{t}+v\dot{\hat{u}_{t}}=\dot{v}\hat{u}_{t}+v\dot{\Theta}\hat{u}_{n}\] |

Before we arrive at our final set of equations, we have one last potential substitution. If a particle is moving along a curved path, the rate at which it is turning (theta dot) will be equal to the velocity of the particle divided by the radius of the path at that point (v divided by rho). Putting this last substitution in, we have our final set of equations with two equivalent options for calculating the accelerations.

| \[a(t)=\dot{v}\hat{u}_{t}+v\dot{\Theta}\hat{u}_{n}=\dot{v}\hat{u}_{t}+\frac{v^{2}}{\rho}\hat{u}_{n}\] |

When using these equations it is important to remember that they are acceleration equations. If we want to know the overall acceleration we would need to add the two acceleration components as vectors. Also if we are given an acceleration that is not in the normal or tangential direction, we will first need to break that acceleration vector down into normal and tangential components before using the above equations. Finally, if we want the velocity or acceleration in directions other than the normal and tangential directions, we will need to use a coordinate transformation.