Centroids of Volumes and the Center of Mass via Moment Integrals

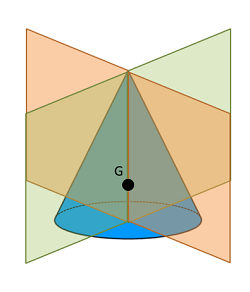

The centroid of a volume can be thought of as the geometric center of that shape. It is often denoted as 'C', being being located at the coordinates (x̄, ȳ, z̄). If this volume represents a part with a uniform density (like most single material parts) then the centroid will also be the center of mass, a point usually labeled as 'G'.

Just as with the centroids of an area, centroids of volumes and the center of mass are useful for a number of situations in the mechanics course sequence, including the analysis of distributed forces, simplifying the analysis of gravity (which is itself a distributed force), and as an intermediate step in determining mass moments of inertia.

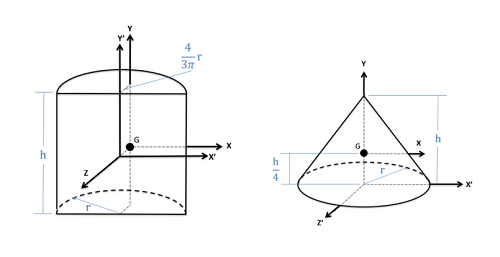

Just as with areas, the location of the centroid (or center of mass) for a variety of common shapes can simply be looked up in tables, such as the table provided in the right column of this website. However, we will often need to determine the centroid or center mass for other shapes and to do this we will generally use one of two methods.

- We can use the first moment integral to determine the centroid or center of mass location.

- We can use the method of composite parts along with centroid tables to determine the centroid or center of mass location.

On this page we will only discuss the first method, as the method of composite parts is discussed in a later section. The tables used in the method of composite parts however are derived via the first moment integral, so both methods ultimately rely on first moment integrals.

Finding the Centroid of a Volume via the First Moment Integral

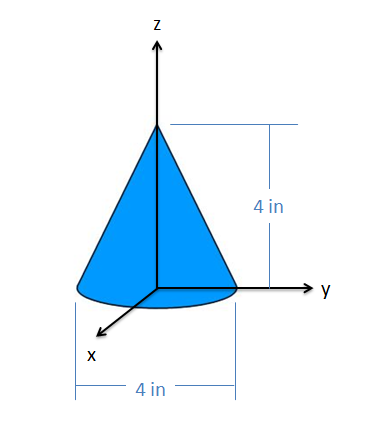

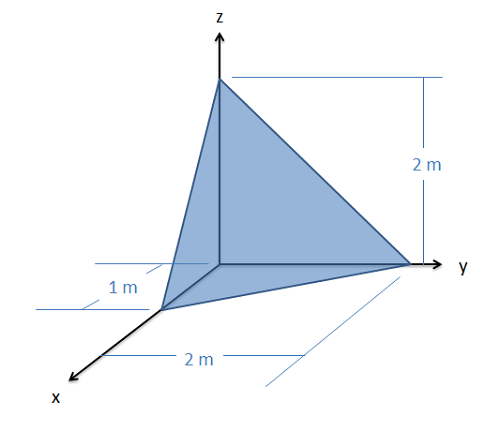

When we find the centroid of a three dimensional shape, we will be looking for x, y, and z coordinates (x̄, ȳ, and z̄). This will be the x, y, and z coordinates of the point that is the centroid of the shape.

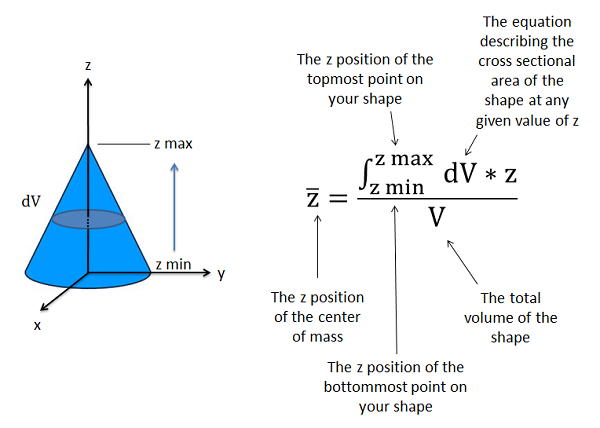

Much like the centroid calculations we did with 2D shapes, we are looking to find the shape's average coordinate in each dimension. We do this by summing up all the little bits of volume times the x, y, or z coordinate of that bit of volume and then dividing that sum by the total volume of the shape. Again we will use calculus to sum up an infinite number of infinitely small volumes. Specifically this sum will be the first, rectangular, volume moment integral for the shape. Working in each of the three coordinate directions we wind up with the following three equations.

| \[C=G=(\bar{x},\bar{y},\bar{z})\] | ||

| \[\bar{x}=\frac{\int_{V}(dV*x)}{V}\] | \[\bar{y}=\frac{\int_{V}(dV*y)}{V}\] | \[\bar{z}=\frac{\int_{V}(dV*z)}{V}\] |

With these new equations we have the variable dV rather than dA, because we are integrating over a volume rather than an area. This represents the rate of change of the volume as we move along an axis from one end to another. The rate of change of the volume at any point on the shape will be the cross sectional area that is perpendicular to that axis times the rate at which we are moving along that axis. Since cross sectional area may vary as we move along the axis, we will need to determine a formula for the cross sectional area at any point along that axis.

Using the first moment integral and the equations shown above we can theoretically find the centroid of any volume as long as we can write an equation to describe the cross section area for each direction. For more complex shapes, however, determining these equations and then integrating these equations may become very time consuming. For these complex shapes, the method of composite parts or computer tools will most likely be much faster.

Using Symmetry as a Shortcut

Just as with 2D areas, shape symmetry can provide a shortcut in many centroid calculations. Remember that the centroid coordinate is the average x, y, and z coordinate for all the points in the shape. If the volume has a plane of symmetry, that means each point on one side of the line must have an equivalent point on the other side of the line. This means that the average value (aka. the centroid) must lie within that plane. If the volume has more than one plane of symmetry, then the centroid must exist at the intersection of those planes.

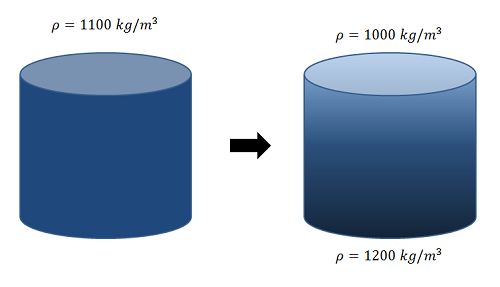

Finding the Center of Mass for Non-Uniform Density Parts

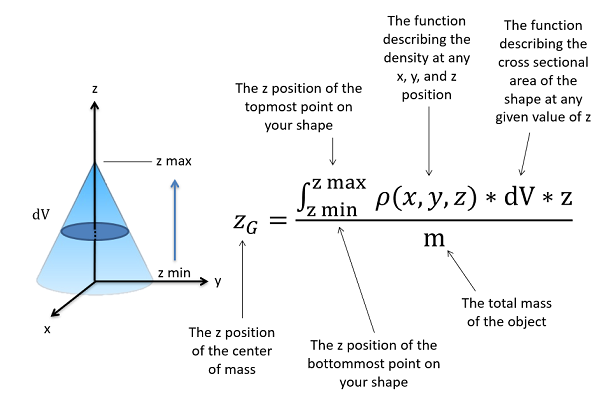

If a body has a non-uniform density, then the centroid of the volume and the center of mass will no longer be the same point. In these cases, we will be integrating with respect to mass, rather than integrating the volume. To do this, we will use something called a density function, which will provide the density (the mass per unit volume) in terms of x,y, and/or z location. In the end, we will also be dividing by total mass, rather than dividing by total volume. The generalized equations for the center of mass are shown in the equations below.

| \[C \neq G\] |

| \[G=(x_{G},y_{G},z_{G})\] |

| \[x_{G}=\frac{\int_{m}(dm*x)}{m}=\frac{\int_{V}(\rho(x,y,z)*dV*x)}{m}\] |

| \[y_{G}=\frac{\int_{m}(dm*y)}{m}=\frac{\int_{V}(\rho(x,y,z)*dV*y)}{m}\] |

| \[z_{G}=\frac{\int_{m}(dm*z)}{m}=\frac{\int_{V}(\rho(x,y,z)*dV*z)}{m}\] |

In instances of uniform density (where the density function did not vary with location and was therefore just a constant), the density constant could be moved outside of the integral. On the bottom, we could also write mass as density times volume, and the density terms on the top and bottom of the fraction would cancel out. That is why for uniform density parts, the centroid and center of mass will be the same point.

When we have a density function that is not a constant, we will have to come up with a mathematical function for the density in terms of x and/or y and/or z locations. If density varies along more than one axis, determining the function and then integrating it may become quite difficult, and computer modeling may be advisable in these situations.

Once you have the density function, you will multiply that by the relevant dV function as discussed earlier on the page and multiply it by the variable for the relevant axis. This entire function is integrated from left to right, bottom to top, or back to front, and then that quantity is divided by mass to find the location of the center of mass.