Impulse and Momentum for a Rigid Body System

As discussed in previous sections, as we move from a particle system to a rigid body system, we need to not only worry about forces and translational motion, but we will also need to include moments and the angular motion. Impulse and momentum methods are no different, and we will begin this chapter by defining linear impulse, angular impulse, linear momentum, and angular momentum.

Linear and Angular Impulse:

As discussed in the impulse-momentum chapter for particles, the linear impulse from a constant magnitude force will simply be equal to the magnitude of the force times the time that that force is exerted for. Because the force is a vector quantity, the impulse is also a vector quantity, where the direction of the force is simply equal to the direction of the impulse. In previous sections we simply called this the "impulse", but in this section we will call it the linear impulse in order to differentiate it from the angular impulse.

| \[\vec{J} = \vec{F}*t\] |

Adapting the idea of impulse into a rotational system simply involves replacing the force in the equation above with a moment. In this case, the magnitude of the angular impulse for a constant magnitude moment will be equal to the magnitude of the moment times the time this moment is exerted for. The direction of the angular impulse vector will simply be equal to the direction of the moment vector. In this resource, we will use a capitol letter K to symbolize the angular impulse.

| \[\vec{K} = \vec{M}*t\] |

In instances where we have non-constant force functions or non-constant magnitude functions, we will simply need to integrate these functions over time to determine the total linear or angular impulse of the force or moment

| Linear Impulse: | \[\vec{J} = \int F(t)dt\] |

|---|---|

| Angular Impulse: | \[\vec{K}=\int M(t)dt\] |

One last important factor to remember when dealing with angular impulse, is that the magnitude of the moment will depend upon the point you are taking the moment about. As such the magnitude of the angular impulse will also depend upon the point you are taking it about. This is important to remember for later, as the impulse and the angular momentum will need to be taken about the same point in order for the angular impulse and momentum equation to work.

Linear Momentum:

As discussed with particles, the linear momentum of a body is equal to the mass of the body times it's current velocity. Since velocity is a vector, the momentum will also be a vector, having both magnitude and a direction. Unlike the impulse, which happens over some set period of time, the momentum is captured as a snapshot of a specific instant in time (usually right before and after some impulse is exerted). The units for momentum will be mass times unit distance per unit time. This is usually kilogram meters per second in metric, or slug feet per second in US Customary units.

It is important to note that, since velocity is not necessarily the same at all points on a rigid body, linear momentum specifically references the velocity at the center of mass.

| Linear Momentum: | \[m*\vec{v_G}\] |

|---|

Angular Momentum:

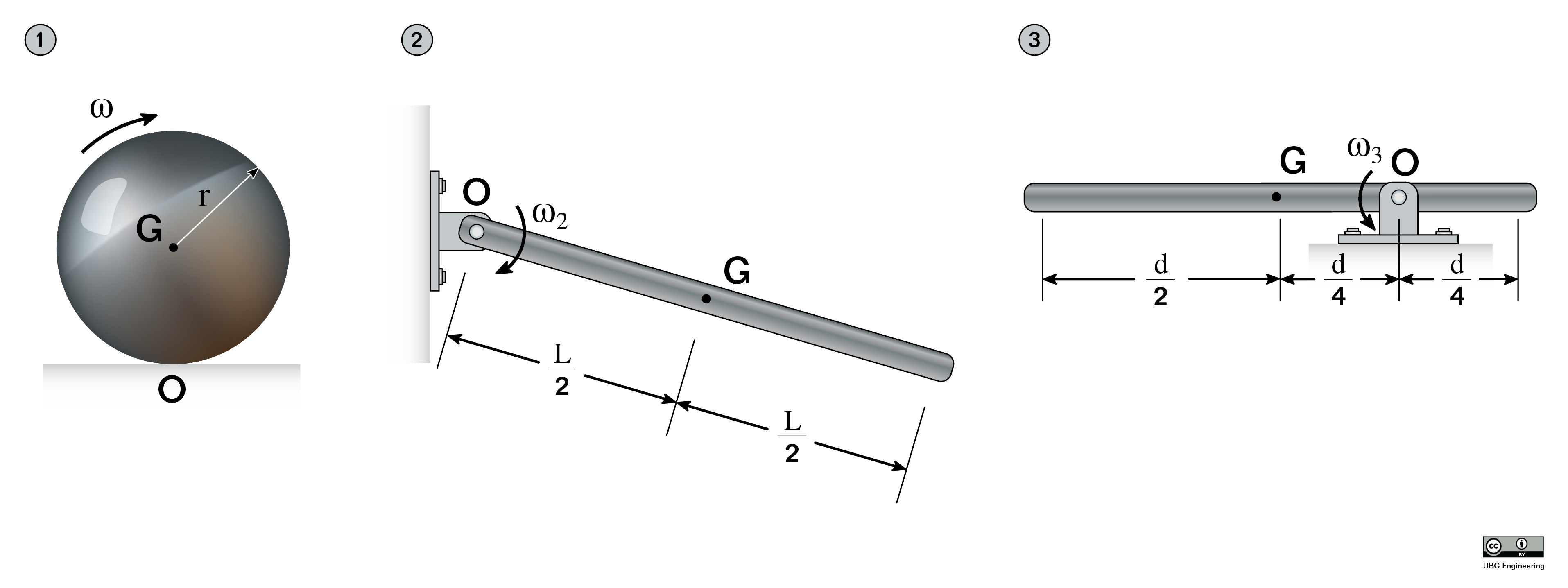

In order to adapt the concept of linear momentum into the concept of angular momentum, we will need to make two adjustments. First we will need to replace the mass of the body with the mass moment of inertia. Second we will replace the velocity of the body with the angular velocity. This leads to the basic formula for the angular momentum of body, which is equal to the mass moment of inertia times the angular velocity of the body.

Because the mass moment of inertia will vary with the point that we take it about the angular momentum will also vary with the point we take it about. Depending on the situation, there may be valid reasons to determine the angular momentum about various points, so keeping that in mind is important.

Some points we may want to find the angular momentum about include the center of mass, some fixed axis of rotation, or an instant center. In all of these cases, we simply need to find the mass moment of inertia about that point, and multiply it by the angular velocity.

| Angular Momentum about the Center of Mass: |

\[I_G*\omega\] |

|---|---|

| Angular Momentum about a Fixed Axis: |

\[I_O*\omega\] |

| Angular Momentum about an Instant Center: |

\[I_IC*\omega\] |

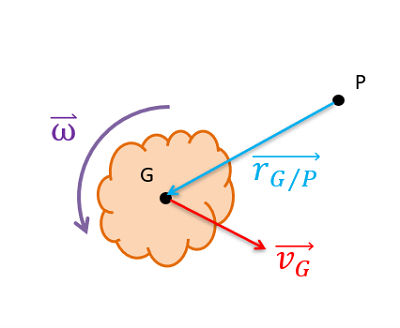

If we wish to find the angular momentum about some other point, such as the point of impact in a rigid body collision, then finding the angular momentum will be slightly more complicated. In this case we will have to take into account the angular momentum due to the rotation of the object, as well as the impact that translation has on angular momentum.

Specifically, the angular momentum will be equal to the mass moment of inertia about the center of mass times the angular velocity of the body, plus the cross product of a displacement vector going from the point of interest to the center of mass with the linear momentum vector of the body. The equation for this is shown below.

| Angular Momentum about Any Point: |

\[I_G * \vec{\omega}+\left( \vec{r}_{G/P}\times m * \vec{v_G} \right) \] |

|---|

As an alternate to the equation above, we can also use an equation that references the mass moment of inertia about our point of interest P, as well as referencing the velocity of point P. This alternate equation is as shown below.

| Angular Momentum about Any Point (alternate): |

\[I_P * \vec{\omega}+\left( \vec{r}_{G/P}\times m * \vec{v_P} \right) \] |

|---|

In the general equations above, we can see how these reduce to a simpler form if there for the center of mass, a fixed axis, or an instant center. First, if the point of interest P is the center of mass (G) then the r vector will be equal to zero and that second term will be zero. Additionally, we can see in the second version of the equation that if the velocity of the point of interest (P) is zero, as it would be for both a fixed axis and an instant center, then the velocity vector would be zero and the second term as a whole would also be zero.