Method of Composite Parts for Moments of Inertia and the Parallel Axis Theorem

As an alternative to integration, both area and mass moments of inertia can be calculated via the method of composite parts, similar to what we did with centroids. In this method we will break down a complex shape into simple parts, look up the moments of inertia for these parts in a table, adjust the moments of inertia for position, and finally add the adjusted values together to find the overall moment of inertia. This method is known as the method of composite parts.

A key part to this process that was not present in centroid calculations is the adjustment for position. As discussed on the previous pages, the area and mass moments of inertia are dependent upon the chosen axis of rotation. Moments of inertia for the parts of the body can only be added when they are taken about the same axis. The moments of inertia in the table are generally listed relative to that shape's centroid though. Because each part has its own individual centroid coordinate, we cannot simply add these numbers. We will use something called the Parallel Axis Theorem to adjust the moments of inertia so that they are all taken about some standard axis or point. Once the moments of inertia are adjusted with the Parallel Axis Theorem, then we can add them together using the method of composite parts.

The Parallel Axis Theorem

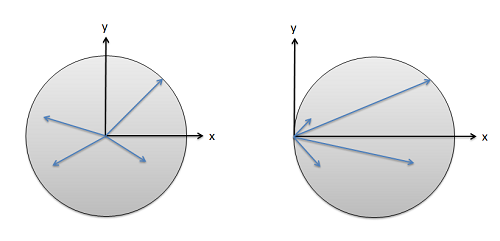

When we calculated the area and mass moments of inertia via integration, one of the first things we had to do was to select a point or axis we were going to take the moment of inertia about. We then measured all distances from that point or axis, where the distances were the moment arms in our moment integrals. Because the centroid of a shape is the geometric center of an area or volume, the average distance to any one point in a body is at a minimum. If we pick a different point or axis to take the moment of inertia about, then on average all the distances in our moment integral will be a little bit bigger. Specifically, the further we move from the centroid, the larger the average distances become.

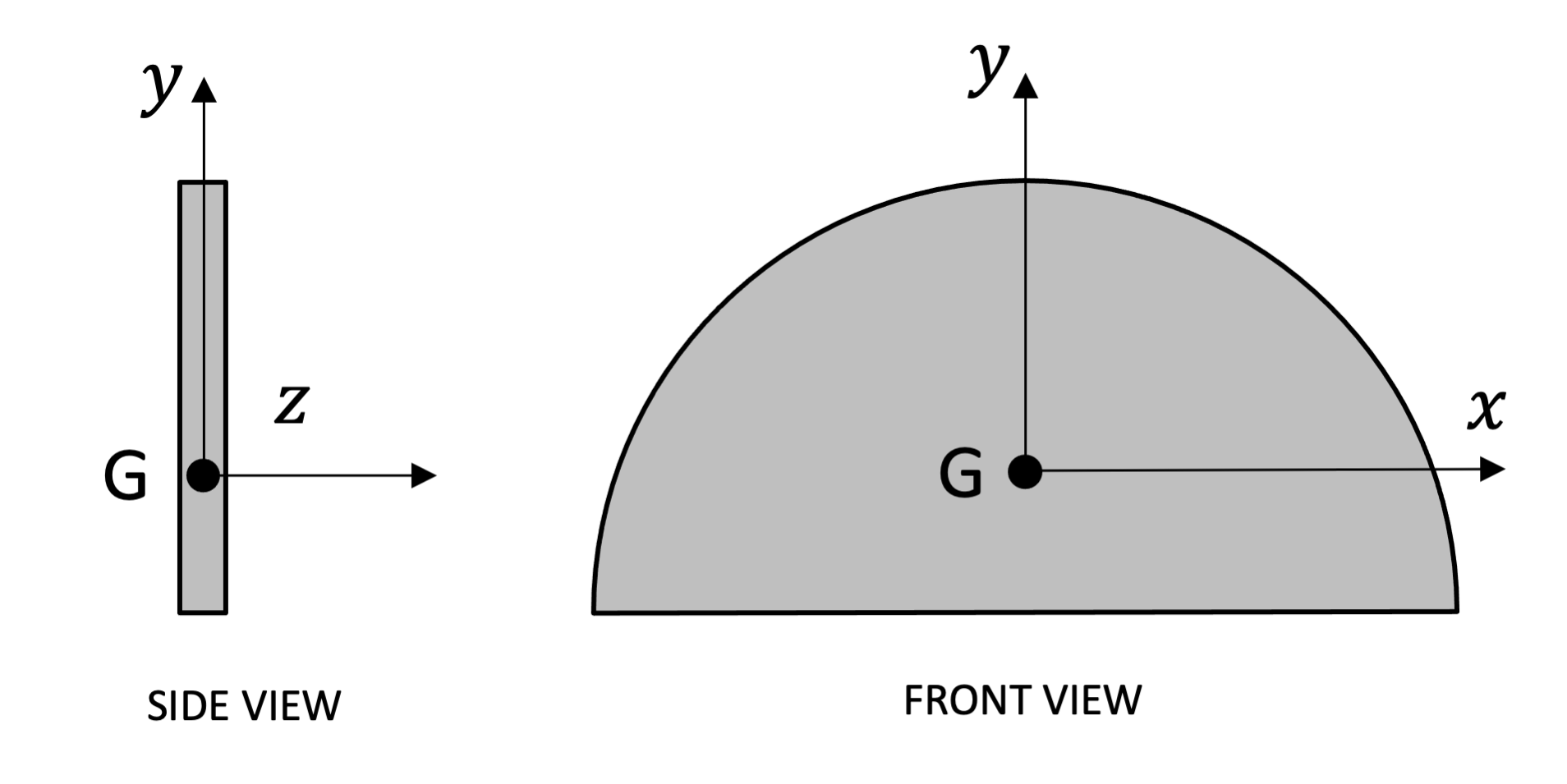

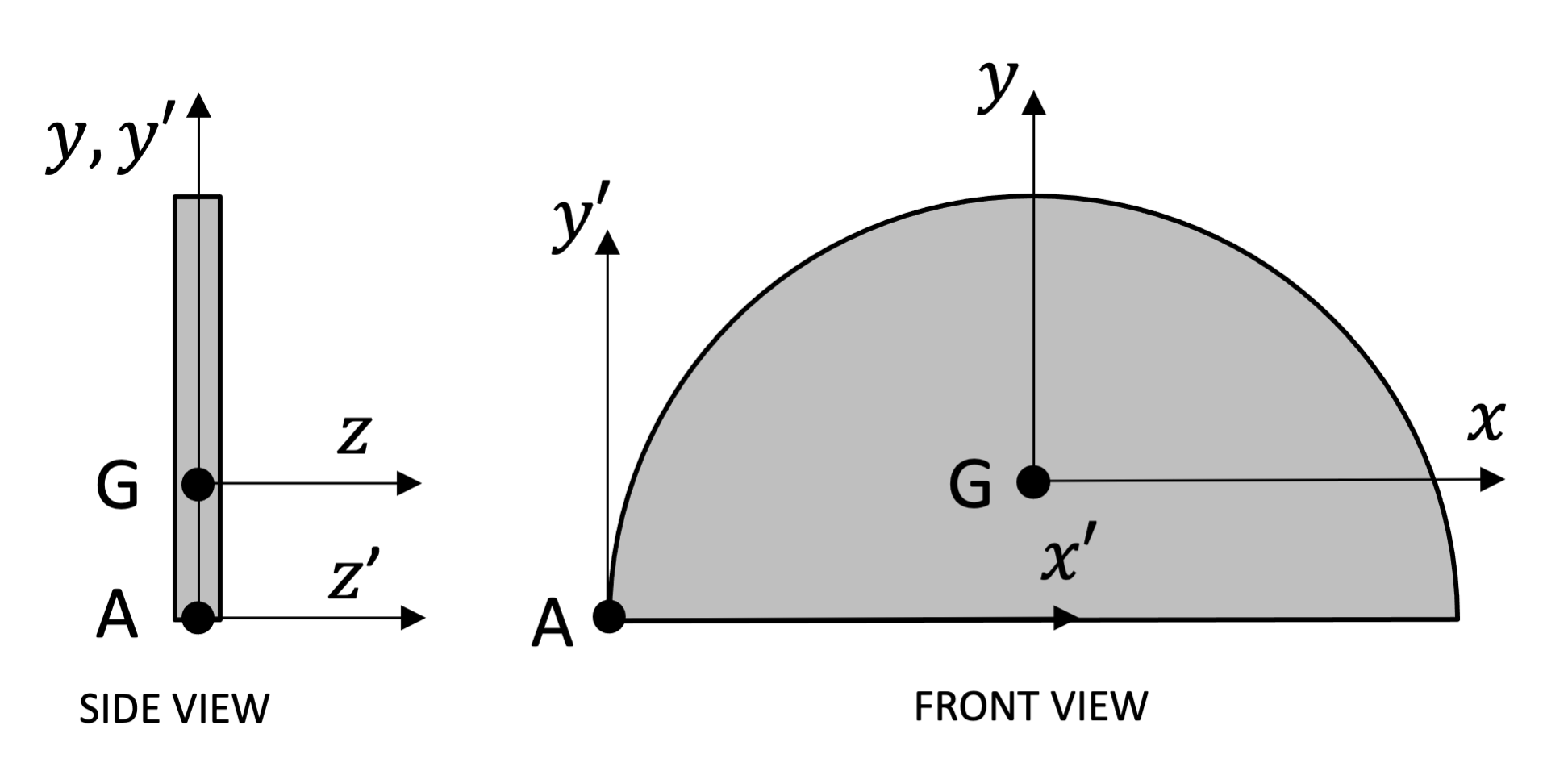

Though this complicates our analysis, the nice thing is that the change in the moment of inertia is predictable. It will always be at a minimum when we take the moment of inertia about the centroid, or an axis going through the centroid (area moment of inertia), and minimum about an axis going through the center of gravity (mass moment of inertia). This minimum, which we will call Ic (area moment of inertia) or IG (mass moment of inertia), is the value we will look up in our moment of inertia table. From this minimum, or unadjusted value, we can find the moment of inertia value about any point Ip by adding an adjustment factor equal to the area times distance squared for area moments of inertia, or mass times distance squared for mass moments of inertia.

| \[I_{xxP}=I_{xxC}+A*r^{2}\] |

| \[I_{xxP}=I_{xxG}+m*r^{2}\] |

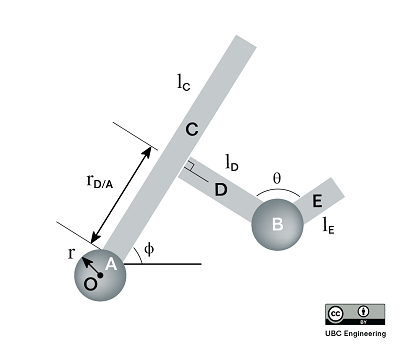

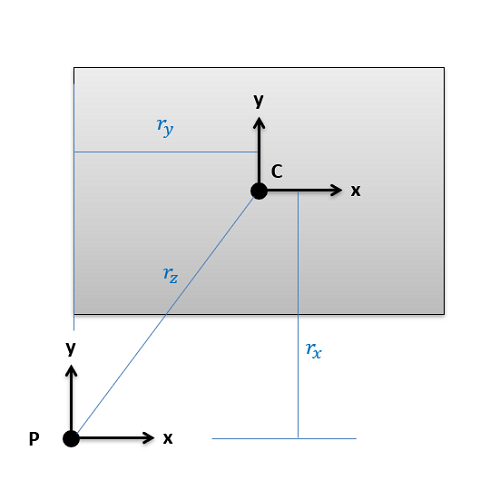

This adjustment process with the equations above is the parallel axis theorem. The area or mass terms simply represent the area or mass of the part you are looking at, while the distance (r) represents the distance we are moving the axis we are taking the moment of inertia about. This may be a vertical distance, a horizontal distance, or a diagonal depending on the axis the moment of inertia is about.

It is really important to note that the parallel axis theorem is only true for Ic or IG - you cannot use the moment of inertia about another point in this formula. It's also clear that the added term will always be positive (area, mass, and the squared distance cannot be negative). This is a reminder that the moment of inertia about the centroid (area moment) or center of gravity (mass moment) is the smallest moment of inertia for that object - about any other axis, the moment of inertia will be greater.

Say we are trying to find the moments of inertia of the rectangle above about point P. We would start by looking up Ixx, Iyy, and Jzz about the centroid of the rectangle (C) in the moment of inertia table. Then we would add on an area times distance squared term to each to find the adjusted moments of inertia about P. The distance we are moving the x axis for Ixx is the vertical distance rx, the distance we are moving the y axis for Iyy is the horizontal distance ry, and the distance we would move the z axis (which is pointing out of the page) for Jzz is the diagonal rz.

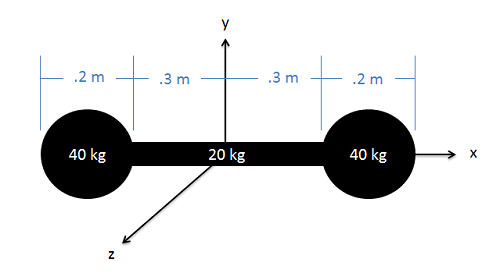

Center of mass adjustments follow a similar logic, using mass times distance squared, where the distance represents how far you are moving the axis of rotation in three dimensional space.

Using the Method of Composite Parts to Find the Moment of Inertia

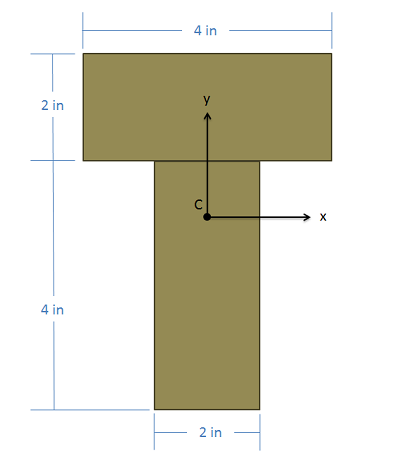

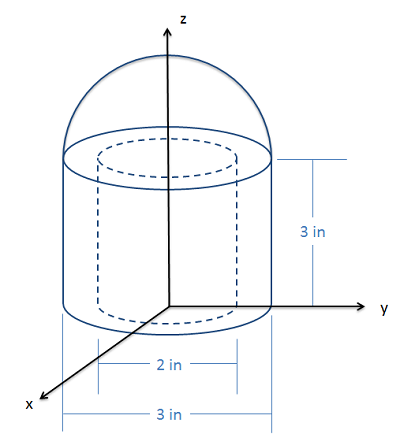

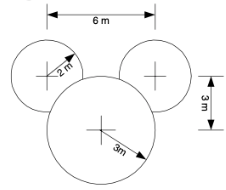

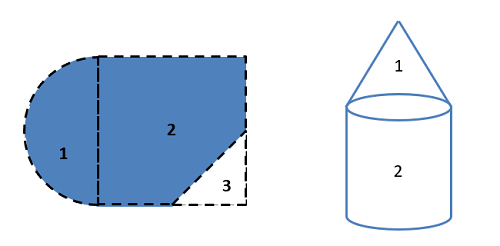

To find the moment of inertia of a body using the method of composite parts, you need to start by breaking your area or volume down into simple shapes. Make sure each individual shape is available in the moment of inertia table, and you can treat holes or cutouts as negative area or mass.

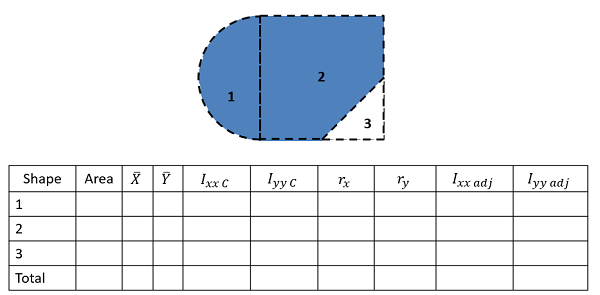

Next you are going to create a table to keep track of values. Devote a row to each part that your numbered earlier, and include a final "total" row that will be used for some values. Most of the work of the method of composite parts is filling in this table The columns will vary slightly with what you are looking for, but you will generally need the following.

- The area or mass for each piece (area for area moments of inertia or mass for mass moments of inertia). Remember cutouts should be listed as negative areas or masses.

- The centroid or center of mass locations (X, Y and possibly Z coordinates). Most of the time, we will be finding the moment of inertia about centroid of the composite shape, and if that is not explicitly given to you, you will need to find that before going further. For more details on this, see the page "Centroids and Center of Mass via Method of Composite Parts".

- The moment of inertia values about each shape's centroid. To find these values you will plug numbers for height, radius, mass, etc. into formulas on the moment of inertia table. Do not use these formulas blindly though as you may need to mentally rotate the body, and thus switch equations, if the orientation of the shape in the table does not match the orientation of the shape in your diagram.

- The adjustment distances (r) for each shape. For this value you will want to determine how far the x-axis, y-axis, or z-axis moves to go from the centroid of the piece to the overall centroid, or point you are taking the moment of inertia about. To calculate these values generally, you will be finding the horizontal, vertical, or diagonal distances between piece centroids and the overall centroids that you have listed earlier in the table. See the parallel axis theorem section of this page earlier for more details.

- Finally, you will have a column of the adjusted moments of inertia. Take the original moment of inertia about the centroid, then simply add your area times r squared term or mass times r squared term for this adjusted value.

The overall moment of inertia of your composite body is simply the sum of all of the adjusted moments of inertia for the pieces, which will be the sum of the values in the last column (or columns if you are finding the moments of inertia about more than one axis).